Executive summary:

- New German CO₂ emission certificates shall be used to achieve climate protection goals.

- The European certificates based on a grandfathering principle (ownership of the certificates by the previous producers) have not worked.

- The ownership of the German certificates lies with the Federal Government, not with consumers.

- The national certificates that have now been introduced will probably work on the producer side because they will no longer receive free certificates (no grandfathering).

- Certificate trading increases product prices and generates revenue for the state (owner of the certificates), but reduces the purchasing power of consumers.

- The emissions cap may be shifted so that certificate prices do not rise too high and acceptance by voters is not lost.

- The concept does not lead to motivated activities of many (consumers have reduced purchasing power and producers have less demand as a result) – but structural change requires effort, competition and creativity.

- Instead, it tends to lead to inefficient governmental decision-making processes with limited knowledge, election gifts and the danger of a culture of complacency.

- This could be avoided if the ownership of CO₂ emission certificates lies with the consumers.

In order to achieve the climate targets agreed in international agreements, the Federal Government is presenting a comprehensive package of measures in the “Climate Protection Programme 2030”. To reduce CO₂ emissions, a national marketplace for CO₂ emission certificates is to be introduced in addition to the European emissions trading system introduced in 2005. Obviously, the existing European emissions trading system has not been sufficiently effective. The question arises as to the reasons for this and whether the right conclusions have been drawn.

Although there are probably a whole range of reasons for rising CO₂ concentrations, it was decided to address the scientifically established main cause and to take measures to reduce the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels. Companies that place heating or motor fuels (based on fossil fuels) on the market will be obliged to hold pollution rights in the form of certificates.

In principle, it is possible to demand the right to emit CO₂ from the product producer or to apply it to the consumer. The Federal Government’s plans are based on the producer, probably also because producers can be controlled more easily.

Holders of certificates can use them or sell them on a marketplace or buy additional certificates. Supply and demand on this marketplace results in a price. This encourages consumers to households and producers to increase efficiency.

The German government’s climate protection programme initially sets a fixed, annually increasing price for CO₂ emissions. From 2026 onwards, a maximum emission level is to be set and trading in certificates for pricing purposes is to be introduced. Companies that place heating or fuel on the market will have to purchase certificates of entitlement from the state by auction or on a trading platform.

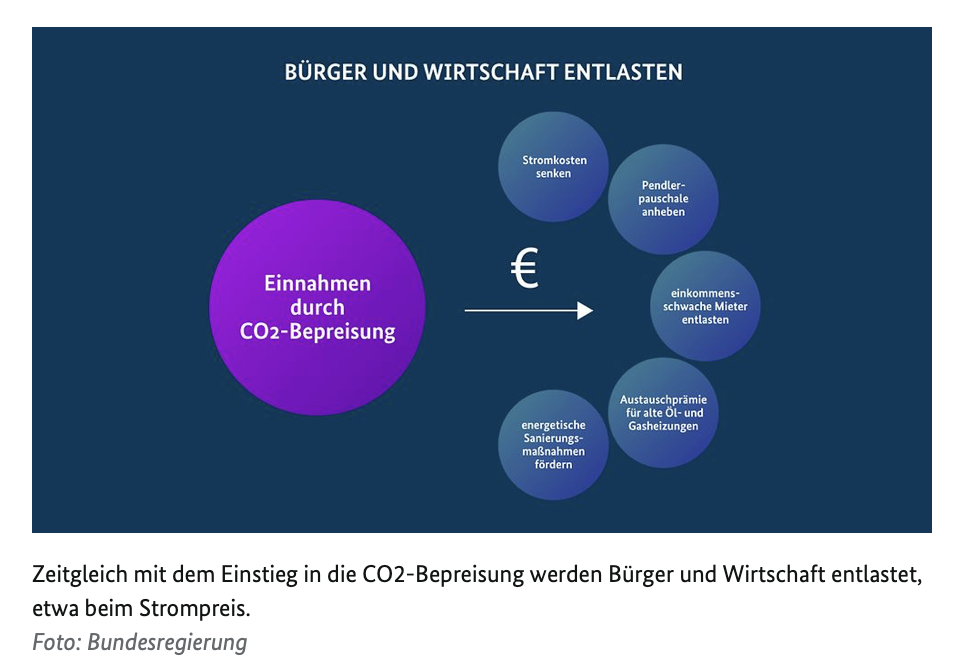

In 2026, minimum and maximum prices set by the state will keep pricing within a limited corridor. In 2025 it is to be determined to what extent such price limits are also sensible and necessary for the period after 2027. Revenues from CO₂ pricing are to be distributed by the state to citizens and companies.

These measures adopted by the Federal Government are judged by various parties to be insufficient. In particular, there is criticism that in the next few years until 2026, it is not the quantity of CO₂ emissions – i.e. the number of certificates – that is to be determined, but rather a price level that is “acceptable” and which in its amount should not yet provide a strong incentive to change behaviour.

There is also criticism that the CO₂ price is a burden on “small” people. For this reason, the state is also trying to offset the burden, e.g. by increasing the commuter allowance. However, this would relativise the desired effect.

It is questioned whether market processes are at all suitable for meeting the challenges of climate change for human civilisation.

For this reason, the effects of market processes and the extent to which governmental steering measures have not been able to successfully replace market processes in the past will be described below.

Market economy creates prosperity and is a learning and discovery process

In a transparent and efficient market, buyers look for subjectively valued goods and compare prices. The purchase is usually made from the cheapest supplier. In competition, suppliers may therefore be forced to reduce their price to the cost of production if there are cheaper suppliers. Producers therefore look for the most efficient ways of generating. Entrepreneurs try to improve comparable products in order to achieve monopoly profits for as long as possible via a unique selling proposition. This drives a learning and discovery process of the market.

Evaluations are subjective in the exchange process, because demand is subjective and third parties cannot answer the question of the standards by which objective evaluations are useful. The question also arises as to who makes “objective” assessments for whom and whether decision-makers have the necessary knowledge to assess the benefits of using goods in specific situations. Under ideal-typical conditions, market processes thus lead to the available production factors being efficiently put to the best possible use.

Prices are information on which people in competition base their decisions. They reflect the knowledge or the assessment of those involved regarding the availability and demand for goods, means of production or even services and intangible goods such as music or literature.

It is crucial for the success of a market process that market participants in a changing imperfect world have the correct estimates and calculations at their disposal, which hopefully prove to be correct or appropriate in retrospect. Well-founded analyses back up these estimates. But in the end, no one has all the available knowledge regarding the supply of production resources, their technical implementation possibilities and the actual needs in the future. Inefficient producers or suppliers of products that are not in demand are dropping out of the market. Accordingly, the barter economy – market economy – reflects the fact that people are part of an evolutionary process and must shape their living conditions in the best possible way in a trial-and-error process.

In societies where there is primarily collective ownership or very centrally controlled economic decision-making processes, there is a serious knowledge problem. This is why socialist societies with collective ownership and state control have not been economically successful. Production processes, production capital and durable consumer goods such as real estate become obsolete and wear out. Adaptation processes to changing living conditions were often sluggish because a centrally coordinated decision-making process was inefficient and imprecise due to a lack of detailed knowledge on the part of decision-makers. Centrally available knowledge is limited and quickly becomes obsolete. It was not voluntary exchange and prices that provided access to products and means of production, but the decisions of authorities. Their knowledge of subjective benefits is lacking and they do not know in detail which production and consumer goods are needed or desired. Hence the statement that the price is the fairest exclusion principle, because no person decides on access, but rather the possibility of disposing of means of exchange that originate from added value created by oneself or by third parties.

Market processes lead to efficient production in line with demand, but they can cause costs or disadvantages for third parties or create benefits that are not covered by a consideration.

Prerequisite freedom of action Exchange needs contracts sanctions and predictable framework conditions for decentralized planning Distribution and justice are not discussed

Market economy not only has a positive effect – External effects

In a market economy, “externalities” arise in situations where production or consumption causes costs or disadvantages for third parties that are not covered by any consideration. An example of an external cost would be when a steel plant blows its exhaust gases into the air and thereby damages the property and health of neighbors. If there are no financial consequences for the polluter, he may deliberately ignore the consequences. The reduction of external costs requires sovereign coordination and can be achieved, for example, through bans and liability.

However, the state can also allow the market to learn and discover. It can do this by creating property rights to public goods, i.e. goods that cannot be separated individually. A historical example of the creation of property rights is the granting of hunting rights. These have been established in history in various forms. The aim was not only to protect game populations, but also to determine who is economically entitled and obliged to the game population. A more recent example is the issue of CO₂ emission certificates as described above, in order to create economic incentives for households and more efficient production in a market process.

European certificates trading from 2005

The theoretical foundations for emissions trading were already laid in the late sixties of the last century. The concept was implemented in the EU from 2005 onwards, with existing producers being granted emission rights according to their previous consumption, which they can sell by reducing their emissions. If emissions were sufficiently reduced, prices did not have to be increased due to additional certificate costs. In fact, certificate prices fell in a long-term trend after the introduction.

The incentive to save was correspondingly relatively low for many years. Competing suppliers without emissions did not have a competitive advantage, so structural change was little promoted. This was referred to as the “grandfathering” principle, which was criticised as not conducive to achieving the desired results even after its introduction.

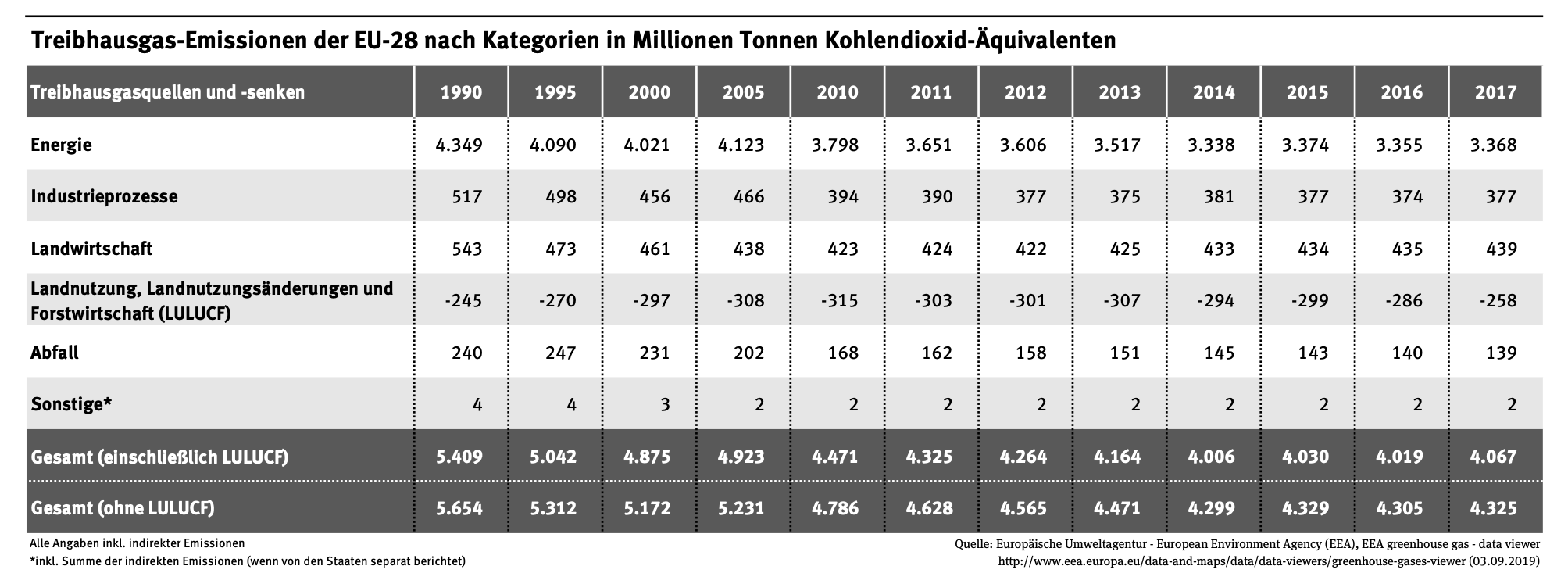

The following statistics show that CO₂ emissions have not decreased for years.

It has taken a long time anyway to apply a property rights approach to limit CO₂ emissions. It is not surprising if a less effective system is then criticized. If the European trading system had produced sufficient effects, a national certificate system for Germany would probably not be necessary at all. A new mistake could further increase emotions.

A national certificate trade as a supplement and to avoid German fines

Die nationalen Zertifikate müssen von Unternehmen erworben werden, die Kraft- und Heizstoffe in to the market. This increases costs. Prices must rise to avoid losses. There is a much stronger price effect than in European certificate trading, where producers have been able to avoid price increases by reducing emissions because they have received enough certificates free of charge for the emissions they have caused. As a result, companies are much more strongly induced to reduce CO₂ emissions than before.

Prices in a market are the result of supply and demand. If the supply of CO₂ emissions to meet targets is severely reduced, prices can be expected to rise sharply. This is especially true if technical alternatives such as an infrastructure for e-mobility are not available in a timely manner.

This leads to very high financial burdens for consumers. The extent to which this is accepted by voters in a democracy is doubtful against the background of protests by “yellow vests” against petrol price increases in other countries.

For consumers, prices increase and their purchasing power decreases, as if an excise tax were levied. Suppliers can sell fewer products. Their sales decrease and this reduces their innovative power. To counteract this, the emissions cap could possibly be shifted so that certificate prices do not rise too high and acceptance by voters is not lost. The achievement of the climate targets would be jeopardised.

In this respect, it appears very challenging to achieve the target set in the German government’s climate protection programme and at the same time to keep pricing within a limited corridor by means of government-set minimum and maximum prices, possibly planned from 2026.

The climate protection programme that has now been launched contains an inherent conflict of objectives for government decision-makers. Maximum prices to maintain acceptance do not fit in with the goal of consistently reducing emissions.

Non-compliance with agreed emission limits is associated with contractual penalties. Similar to the penalties never applied in the context of the monetary union for violating the EU convergence criteria, it is to be feared that the payment of such penalties will not be socially accepted. In the monetary union, taxpayers from deficit countries who are under pressure anyway would ultimately have to finance these payments. A lack of acceptance is even more likely if consumers have already had to put up with price increases and then further levies are needed to pay fines. It is then also open who will ultimately pay to whom and what a recipient will do with the penalties received.

The state uses the revenues from the auctioning of the allowances in budgetary decisions. There is a risk that service provision will be burdened and transfer income generated. This may reduce the acceptance of such a system among those who are supposed to promote structural change in a motivated, creative and competitive manner. This would be the case, for example, if such income were to be used to finance rising pension costs. Parliamentarians decide whose purchasing power is increased. However, they cannot force that and for what purpose received funds lead to economic demand. This would be the case, for example, if subsidy programmes for building insulation were not taken up. As a result, such a system can lead to inefficient governmental decision-making processes with limited knowledge, election gifts and the danger of a culture of complacency.

People may feel that their free development of personality is reduced too much and would at least within limits want to decide for themselves what they use their natural right to emit CO₂ for. However, this effect could be avoided if CO₂ pollution rights were assigned to people.

CO2-pollution rights as civil right, design and economic effects

If citizens receive property rights on an equal footing (per capita), they can sell their certificates and finance higher product prices on balance from the proceeds. The purchasing power is maintained. Consumers budget and decide what CO₂ emissions are used for. Producers are even more induced to counteract necessary price increases through innovation in order to convert the continuing purchasing power into sales – product sales.

An example:

A gas supplier would have to buy certificates, which might significantly increase the price of his product. With the income from the sale of its certificates, a homeowner can finance a higher price for gas for heating. If he heats his house without fossil fuels, e.g. with geothermal district heating, there will be no price increases for him, because the supplier can keep the price of his product the same. As a result, he receives purchasing power-increasing income from CO₂ emission certificates. He can thus purchase other products and decide which products he wants to use the income from the sale of his emission allowances for. These can also be products for which price-increasing CO₂ emissions cannot be avoided, for example if he absolutely needs them despite the environmentally harmful effects.

For the owner of a house heated with gas there is an incentive to change the heat supply, because then he would also have income with which he can purchase other products. For the gas supplier, the need arises to reduce the need and thus the costs for CO₂ emission certificates through new technologies in order to make his product more competitive again. In the end, CO₂ is used efficiently for the product with the highest benefit.

A holder of CO₂ emission certificates has an incentive to obtain the highest possible price for his certificates. In order to counter speculation and possible supply bottlenecks caused by hoarding CO₂ emission certificates, an expiration date for a certificate is probably necessary.

Particularly environmentally friendly certificate holders could refrain from selling their certificates and thus further reduce the volume of emissions permitted by the state.

If individuals have a personal right to CO₂ emissions per capita, this can lead to income for those who consume less CO₂ than they have certificates. They generate income or assets. Some time ago, it was proposed to issue certificates per capita and to make trading in CO₂ emission certificates an instrument of development aid. People with particularly low CO₂ consumption could possibly receive a “basic income” from sold certificates

It would therefore be more effective if the state were not the original owner of the certificates, but if the CO₂ certificates were distributed to citizens and the state as consumers. These would be induced to budget and would decide what CO₂ certificates are used for when purchasing a variety of products.

Such an approach to an individually responsible reduction of CO₂ emissions could be economically advantageous, efficient and probably also fair and socially acceptable.

A limited right to emit CO₂ could be understood as a human right. Possibly this would also be the case from a constitutional perspective, because Article 2 of the German Constitution guarantees the free development of the personality. This could also include the right to emit CO₂. Article 14 – the right to property – could also be a norm that would justify a claim.

Munich, January 2020

Leave a Comment