Executive summary:

- The EU Emission Trading Scheme (EU ETS) introduced CO2 emission certificates in 2005 on the basis of a grandfathering principle (ownership of the certificates by the previous emitting companies) and did not have sufficient effects. [1]

- Since 1.1.2020, climate protection targets are to be achieved more effectively with German CO2 emission certificates.[2]

- A fixed and annually increasing price is determined for the certificates until 2025. Also a cap for emissions is envisaged. From an economic point of view, however, it is not possible to set a fixed cap on emissions and at the same time set a price. This would at best be possible if production were to be controlled.

- More effective emission caps will be introduced from 2026. Prices could and probably should not be capped to maintain the price mechanism and ensure effective supply and demand dynamics. Whether and how this is politically feasible is a matter of debate.

- German certificates are issued by the state and must be purchased by producers from the state if needed. On a secondary market, certificates can be sold by third parties who do not need their certificates.

- The national certificates now introduced are likely to cause efforts on the production side to significantly reduce CO2 emissions, because producers do not receive free certificates through “grandfathering”. CO2 emissions lead to rising costs that cannot be easily compensated by higher prices.

- The sale of certificates generates revenues for the state (owner of the certificates), but reduces the purchasing power of consumers. As a result, producers may face less private demand for their products.

- Financially powerful and creative consumers who optimize their utility under budget constraints and adjust the use of goods are an important prerequisite for a learning and discovery process in markets.

- On the one hand, the state announces that it will use the revenue to sponsor specific climate protection measures or implement them itself. On the other hand, however, purchasing power is to be redistributed to the consumers in a certain manner. A political struggle over this will probably lead to compromises, but these will interfere with the planning of market participants. Predictable price signals through transparent certificate trading and consumers using their purchasing power for goods and services would promote individual planning by producers and users.

- Lowering emissions caps may not be feasible, despite other plans, because if certificate prices are too high and there is a significant loss of wealth by part of the population, their acceptance by voters would be undermined.

- The design of CO2 certificates in Germany makes individual planning more difficult and does not lead to incentivized activities by many market participants. Structural change, however, requires broad-based effort, competition and creativity.

- Instead, what tends to emerge are unpredictable and inefficient government decision-making processes under limited knowledge, electoral giveaways, and the danger of a culture of populism.

- This could be avoided if the ownership of CO2 emission certificates rested instead in the hands of the consumers.

- Certificate trading, in which consumers receive the certificates, is – contrary to what many politicians think – is not a zero-sum game, but rather influences an evolutionary process of learning and discovery without expanding the size of the state.

Which regulations are in place?

In order to achieve the climate targets agreed in international agreements like the Paris Agreement of the United Nations[3], the German government presented a comprehensive package of measures in the “Climate Protection Program 2030”. To reduce CO2 emissions, a national trading scheme for CO2 emission certificates is to be introduced in addition to the European emissions trading scheme introduced in 2005. Apparently, the existing European emissions trading scheme has not had sufficient effects. The question arises as to what the reasons are and whether the right consequences have been drawn from this. Some drawbacks will be discussed later.

Although there are probably a number of reasons for rising CO2 levels, it was decided to address the scientifically identified main cause and to focus the measures on reducing the extraction and use of fossil fuels. Companies that sell heating or motor fuels (based on fossil fuels) are to be obligated to hold pollution rights for them in the form of certificates. The certificates will be issued by the state, which will receive the revenue from the certificates.

In principle, it is possible to charge the producer for the right to emit CO2 or the consumer. The government’s plan focuses on the producer, probably also because producers can be controlled more easily.

Holders of certificates can use them or sell them on the market or buy additional certificates. A price is created by supply and demand on this market.

The German government’s climate protection program initially sets a fixed and annually rising price for CO2 emissions. From 2026, a maximum emission volume is to be set and the trading of certificates is used for price formation. Companies that use fossil fuels will have to purchase certificates from the state or on a trading platform.

Until 2026, government-set minimum and maximum prices are to be used to keep price formation within a limited corridor. In 2025, it is to be determined to what extent such price limits are also appropriate and necessary for the period from 2027. Revenues from CO2 pricing are to be redistributed by the state to citizens and companies.

These measures adopted by the German government have been assessed as inadequate by various groups. In particular, it has been criticized that the amount of CO2 emissions – i.e. the number of certificates – will not be determined in the next few years until 2026, but that a price level is to be determined that is “acceptable”. It is argued that at this price level it is not yet likely to provide a strong incentive to change behavior. In April 2021, the German Constitutional Court echoed this criticism and called upon the legislature to adopt more extensive measures for climate protection.

Another criticism is that “poor” people are being adversely affected by the CO2 price. For this reason, the state is also trying to compensate for the cost, e.g. by increasing the commuter tax relief. However, this would offset the intended effect.

Furthermore, it is questioned whether market processes in general are appropriate to address the challenges of climate change for human civilization.

For this reason, the dynamics of market processes and the historic failure of government intervention to successfully replace market processes will be discussed below.

A market economy creates prosperity and is an evolutionary process of learning and discover

In a transparent and efficient market, buyers seek subjectively valued goods (subjective value theory) [MENGER] and compare prices to optimize individual utility. Individual utility considerations and curiosity are accompanied by a process of learning and discovery about the properties and possible uses of products.

Products are normally purchased from the lowest-cost supplier, given the same quality. In a competitive market suppliers may be forced to lower their price to the actual cost of production if there are cheaper suppliers. Therefore producers are constantly looking for the most efficient production methods. Inefficient suppliers drop out of the market. Entrepreneurs try to improve comparable products in order to obtain a unique selling position for as long as possible.

Supply and demand drive a process of learning and discovery in the use and production of goods and services.

Prices result from supply and demand. They are information on which individuals, competing in the market, base their decisions on. They reflect the knowledge or the assessment of actors about the supply and demand for goods, means of production or even services and intangible goods such as music or literature.

It is crucial for the success of market processes that market participants use prices to make calculations and form expectations about the supply and demand in a changing world and that these subsequently prove to be correct or appropriate.

Valuations in the exchange process are subjective because demand is subjective and third parties cannot judge the standards by which subjective valuations are made. In the case of “objective” assessments, the question would also arise as to whom performs them and whether the decision-makers have the necessary knowledge to assess the benefit of a use of goods at a specific time and place.

Sound analyses can back up the assessments of decision-makers, but ultimately no one has all the existing knowledge regarding the supply of means of production, their technical implementation possibilities and the actual demand in the future. Accordingly, the exchange economy – market economy – reflects the fact that people are part of an evolutionary process and shape their living conditions in the best possible way in a trial-and-error process.

However, erroneous developments do not normally have an adverse societal impact, but only an individual or limited impact on the respective group, where those responsible are liable and can lose the control over the means of production or goods if losses are too high. Erroneous developments primarily have consequences for those acting. Only in serious cases do they have an impact on the society as a whole via chain reactions. The assessment of potential negative consequences leads to corresponding avoidance efforts and goes hand in hand with individual financial liability. Because of the individual attribution of failure consequences and the principle of personal responsibility, societies organized in a market economy were extraordinarily adaptive in the clash of cultures and thus ultimately successful.

In societies where there is primarily collective ownership of the means of production and centrally controlled economic decision-making there is a serious problem of incentives, organization and knowledge.[4] This is why socialist societies with collective ownership of the means of production and a high level of state control were also not very successful economically:

Political decision-making processes are necessarily oriented first towards maintaining power and balancing interests between different special interest groups and secondarily towards the broader individual benefit. Production processes, production capital and durable consumer goods such as real estate became obsolete and wore out. Adaptation processes to changing living conditions were often sluggish because the centrally coordinated decision-making process was inefficient and imprecise due to a lack of detailed knowledge among decision-makers. Centrally available knowledge was limited and quickly outdated. In socialist societies, it was not voluntary exchange and prices that provided access to products and means of production, but the directives of authorities. These lacked knowledge about subjective utility valuations and which production and consumption goods were needed or wanted. As a result, users did not receive products that they subjectively appreciated.

It becomes less attractive to provide one’s own services in exchange for goods and services that are not subjectively appreciated. In centrally planned economies, the motivation to work hard, take risks, and innovate decreases.

Contribution of consumers to the learning and discovery process in markets

In neoclassical economics, a purely utility-oriented, static and rational decision-making logic of economic agents is assumed in the fiction of homo oeconomicus.[5] This does not suffice.

For far-sighted and demanding users of goods and services, it is obvious to base their subjective valuations in pricing not only on the immediate personal, material utility but also on more far-reaching and indirect utility as well as on immaterial and emotional aspects and to include these in their subjective valuation.

In their entrepreneurial learning and discovery process, producers benefit from creative and demanding users who require producers to develop and manufacture special individualized and innovative products. In this process, producers are confronted with their own ideas about products. These are optimized in an interdependent process between users and producers.

Many of such products and processes are complex. They require financially empowered consumers. Particularly attractive products are often copied later, so production costs are reduced and they become commonly available.

Financially empowered, creative, and demanding consumers are, in general, an important prerequisite for the learning and discovery process of companies. E.g. organic stores did not emerge by government design, but emerged by the interplay between consumer preferences and creative entrepreneurs.[6]

Subjective assessments can only be made if products and their properties can be assessed when they are exchanged. Often, the utility only becomes apparent later and is influenced by the usage of the product. Therefore, suppliers are liable for defects and risks of products to the user.

For the learning and discovery process on economic usefulness in markets, the use of the product and the experiences of learning users on the actually achievable utility are an important component. If negative experiences spread, alternative solutions are explored.

In this regard government decision-makers have an information shortfall. This can lead to erroneous assessments of economic planning measures and regulations.[7]

To the extent that government decision-makers impose regulations on the purchase of goods and services, the exchange is no longer voluntary if consumers do not consider the products produced in return to be useful. The same applies if subsequent modifications are demanded to alter the properties of products already purchased and in use (e.g. insulation of already constructed houses). However, coercion might be required to enforce subjectively non-useful exchanges. This could be justified in a democratic process on the basis of supposedly “objective valuations”. However, acceptance is questionable in a democracy.

Economic activity can increase as a result of regulations and prohibitions. Revenues in a country’s economy (gross national product) increase. Politically, an increased gross national product is seen by many as a successful policy. Whether the individual (subjective) utility increases as a result is, however, an open question. If the subjective utility does not increase, the social question arises as to why people should work for such “growth” and consume resources.

A market economy does not only increase utility – external effects

“Externalities” arise in a market economy in situations where production or consumption causes costs or disadvantages to third parties, which are not internalized. An example of an externality would be when a steel mill blows its waste gases into the air, damaging the property and health of nearby neighbors. If there are no financial consequences for the polluter, he may deliberately ignore the consequences. Reducing external costs can be achieved by government regulations like prohibitions and the explicit definition of liability, but also other coordination mechanism departing from the common seeing-like-a-state mentality are imaginable.[8]

However, the state can also design a regulatory environment enabling a process of learning and discovery by economic agents. It can do this by creating property rights to public, i.e. individually inseparable goods (property rights approach). A historical example of the creation of property rights is the granting of hunting rights. These have been established in various forms throughout history. The aim was not only to protect the wild stock, but also to determine who is economically entitled and liable with regard to the wild stock.

Certificate trading

The theoretical basis for emissions trading emerged in the late 1960s [DALES].

With the determination of property rights in the form of pollution certificates and the requirement for producers to purchase them if they generate harmful negative externalities, costs are created. Prices increase, forcing producers to deal efficiently with pollution in a competitive market economy. The interactive learning and discovery process between users and producers is triggered.

If ownership of the certificates is assigned to consumers, they either receive sales proceeds from the certificates or must redeem them when purchasing products. Consequently, they economize with the funds they receive. They decide which products they assign the subjectively highest utility to and for which products they accept higher prices. Product properties become clearer in terms of their collective utility as a result of the price increases. The learning and discovery process of consumers concerning the properties and possible uses of products is stimulated. The demand for goods and services with high pollution effects and low subjective utility decreases. With a consistent limitation of pollution rights and appropriate control, pollution decreases in a predictable way. Initial price increases are mitigated by behavioral adjustments in the selection and use of subjectively useful goods and services. This works through an interdependent process between consumers and producers, which adjust production and usage behavior. Making an effort, innovating and providing services in order to obtain subjectively useful goods continues to be attractive.

Alternatively, the pollution certificates can be allocated to the producer according to the “grandfathering” principle. The producers initially receive sufficient certificates so that there are no price increases. By lowering the amount of certificates issued over time, an incentive is created among these producers to reduce pollution. However, if innovative suppliers of alternative products do not know whether they will receive certificates, they cannot fully develop their competitive advantage because they do not have price advantages. Existing production structures could continue as long as they receive sufficient certificates.

If the state assigns ownership of the certificates to itself, producers must purchase them from the state. With the revenues, the state can make expenditures and bring about utility on the basis of supposedly “objective valuations”. However, government decision-makers are often not primarily focused on achieving the best and most efficient effects, but on gaining as many votes as possible in the next elections. When it comes to the use of the revenues received, the knowledge and organization problem described above exists in governmental economic decision-making processes. Companies are oriented towards government contracting authorities and their directives. The learning and discovery process between users and producers in the development of innovative products is sidelined. The knowledge problem about the supply and utility of goods and services reduces productivity. Subjectively less useful goods emerge and their use may have to be enforced. The motivation to make individual efforts to improve the capabilities in the exchange of services decreases.

European certificate trading from 2005

The grandfathering concept was implemented in the EU from 2005 onwards. Existing producers received emission certificates in line with their previous consumption, which they could sell if their emissions were reduced. If emissions were reduced sufficiently, prices did not have to be increased due to additional certificate costs. In fact, certificate prices fell in a sustained trend after the introduction.

Accordingly, the incentive to reduce emissions was relatively low for many years. Competing suppliers without emissions had no competitive advantage, so that structural change was hardly promoted. This was referred to as the “grandfathering” principle, which was criticized at the time of its introduction as not being helpful.

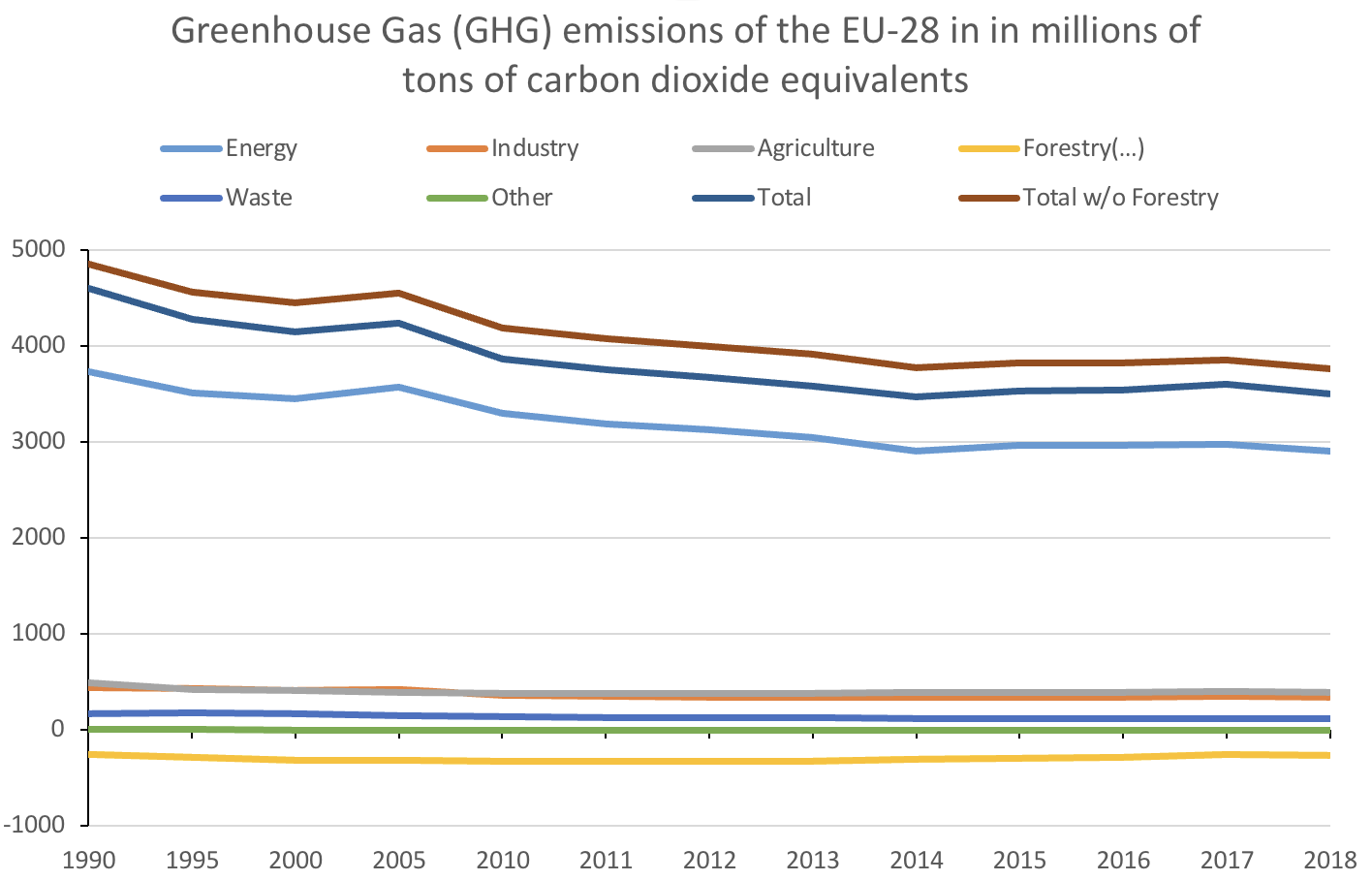

The following figure shows that CO2 emissions declined before and especially after the introduction of the EU ETS in 2005. However, only until 2012. Since then, further progress has been very limited.

In any case, it has taken a long time to apply the property rights approach to limiting CO2 emissions. It is hardly surprising if a barely effective system is criticized. If the European trading system had produced sufficient effects, a national certificate system for Germany would probably not be necessary.[9]

A new flaw in the design of certificates could further increase resentments and social tensions.

A national certificate trade to complement and avoid German financial penalties

The national certificates must be purchased by companies that sell motor or heating fuels. This increases costs. Prices must rise to avoid losses. There is a much stronger price effect than through European certificate trading, in which producers were able to avoid price increases by reducing emissions because they received sufficient certificates free of charge for the emissions they produced. This gives companies a much stronger incentive to reduce CO2 emissions than before.

In a market economy, prices are the result of supply and demand. If the supply of CO2 emission rights to achieve the climate targets becomes severely scarce, prices can be expected to rise sharply. This is particularly true if technical alternatives such as an e-mobility infrastructure are not available in a timely manner.

This leads to high financial burdens for consumers. The extent to which this is accepted by voters in a democracy is doubtful against the backdrop of protests by “yellow vests” against gasoline price increases in France.

For consumers, prices increase and the resulting lower purchasing power is similar to the levying of a consumption tax. Suppliers can sell fewer products. Their sales fall and this reduces their innovative strength.

To counteract this, the emissions cap, envisaged in the climate protection program 2030, could possibly be postponed so that certificate prices do not rise too high and their acceptance by voters is not lost. Achieving the climate targets would be jeopardized.

In this respect, it appears to be a major challenge to achieve the target set out in the German government’s climate protection program and at the same time to keep price formation within a limited corridor by means of minimum and maximum prices that may be set by the government from 2026 onwards.

The climate protection program now in place involves an inherent conflict of objectives for government decision-makers. Maximum prices to maintain acceptance do not fit with the goal of consistently reducing emissions.

Non-compliance with agreed emission limits is subject to penalties. Similar to the penalties never applied within the European monetary union for violating the Maastricht criteria of excessive deficits and debt levels, it can be expected that the payment of such penalties will not be socially acceptable. In the monetary union, taxpayers from deficit countries who are under pressure would ultimately have to finance these payments. A lack of acceptance is even more likely if consumers have already had to accept price increases and then further payments in the form of penalties are imposed. It is also unclear who will ultimately pay to whom and what a recipient will do with the penalties received.

The state uses the revenue from the auctioning of certificates as part of budgetary planning decisions. There is a risk that growth impulses by productive entrepreneurs will be burdened and transfer income (redistribution) will be created. This can reduce the acceptance of such a system among those who are supposed to drive the structural transformation in a motivated, creative and competitive process. This would be the case, for example, if the revenues were used to finance rising pension expenses. Ultimately, parliamentarians decide whose purchasing power is increased. However, they cannot enforce where funds received lead to economic spending. This would be the case, for example, if subsidy programs for building thermal insulation were not utilized.

Citizens may feel that their free individual development is reduced too much and would want to decide for themselves, at least within limits, how they use their natural right to emit CO2. However, this effect could be avoided if CO2 pollution rights were allocated directly to the citizens.

CO2 pollution rights as a civil right

If citizens receive property rights on an equal basis (per capita), they can sell their certificates in a trading system and finance higher product prices from the proceeds. Purchasing power is maintained.

From a governmental perspective, this could be seen as a “zero-sum game”. However, real effects are created: Consumers economize and decide for what their limited CO2 emission rights will be used. They are induced to increase their efforts if there are still subjectively attractive products available in the exchange process and they can use them innovatively. Producers are even more incentivized to reduce CO2 emissions and to counteract necessary price increases through innovation in order to convert the existing purchasing power into sales.

An example:

A gas supplier would have to purchase certificates, which may significantly increase the price of its product. With the revenue from the sale of his certificates, a homeowner can finance an increased price for gas.

If he heats his house without fossil fuels, e.g. with geothermal heating, there is no price increase for him, because the heating supplier can leave his product at the same price. As a result, he receives income from the sale of his CO2 emission certificates that increases his purchasing power. He can use it to purchase other products and decide for which products he will use the income from the sale of his emission certificates.

These can also be products for which price-increasing CO2 emissions cannot be avoided, for example if he desperately needs them despite the environmentally adverse effects.

For the owner of a house heated with gas, there is an incentive to change the heating system, because then he would have income with which to purchase other products.

For the gas supplier, the need arises to reduce the amount demanded and thus the cost of CO2 emission certificates through new technologies in order to make its product more competitive again. Ultimately, the CO2 emission certificate is efficiently used for the product with the highest benefit.

Individual opportunities and risks of private ownership of pollution certificates

Particularly environmentally friendly holders of certificates could forego selling them and thus additionally reduce the volume of emissions permitted by the state.

If individuals are entitled to a personal right to CO2 emissions per capita, this can lead to income for those who produce fewer CO2 emissions than certificates they received. For them, income or wealth is created.

One could imagine issuing certificates per inhabitant of the earth and turning trading of CO2 emission certificates into an instrument of development aid. People with particularly low CO2 emissions, such as cyclists in larger cities, could possibly receive a “basic income” from sold certificates.

Capable entrepreneurs could receive more certificates, in addition to government allocation, by taking actions that remove CO2 from the atmosphere (negative emissions). If they can prove that CO2 is being removed from the atmosphere, additional certificates can be issued for such activities without increasing pollution levels above the specified cap. High certificate prices would make such activities attractive and the price increase would be mitigated.

The state would also be forced to economize on CO2 emissions itself, because it would have to obtain the certificates needed for its own needs via taxes (either payment in currency or in the form of a certificate). CO2 emissions would not be a cost-free good for the state.

However, private ownership of emission rights also bears risks:

An owner of CO2 emission certificates has an incentive to obtain the highest possible price for his certificates. This could lead to certificate hoarding and speculation. Hoarding of certificates would be useful with regard to CO2 emissions. Nevertheless, it would have to be examined whether an expiration date for a certificate would be necessary in order to make speculation more difficult. Other measures to ensure a functioning certificate market should also be studied.

Summary

If the ownership of pollution certificates does not rest with the individual, the anticipated favorable free-market effect will most probably not emerge.

Instead, there is a loss of purchasing power and less attractive goods and services are offered.

There are conflicting views on whether a “climate emergency” exists and whether drastic action is needed. If societies choose to combat a rise in temperatures by reducing CO2 emissions, effective means are needed. Attempting to do this through government design with commands and prohibitions, rather than relying on the price mechanism with consistently set caps on CO2 emissions and decentralized learning and discovery processes, will not lead to the desired goals due to knowledge deficits among government decision makers.

It is crucial to make certificate trading effective and unleash the creativity and innovation capacity of entrepreneurs. Otherwise, a rejection of the market and emissions trading could be the result. The climate targets would not be achieved.

Prosperity would be reduced, probably more than necessary. Political polarization could be the result.

P.S.:

A limited right to emit CO2 could be understood as a human right. Possibly, this would also be required from a constitutional perspective, because Article 2 (1) of the German Constitution guarantees the free development of the personality. This could also include the right to emit CO2. Article 14 of the German Constitution – the right to property – could also be a legal norm.

[1] During phase 1 (2005-2007) and phase 2 (2008-2012) of the EU ETS the mayor part of certificates was allotted to the industrial and energy sector for free. The specific amount of certificates allocated was based on the historical emissions of the industrial and energy sector (grandfathering). See details on page 42 of the ETS handbook. In 2012 also the inner EU air traffic was included in the EU ETS.

[2] The German climate protection program now extends to sectors, where fossil fuels are used (gasoline and heating oil consumption) and which are not yet included in the EU ETS.

[3] The details of the Paris Agreement can be reviewed here: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement.

[4] During the early 20th century, the possibity of a rationalization of production by central authorities was discussed in the socialist calculation debate. Mises [MISES] argued that with the abolition of private property and ultimately the price system the coordination of economic activity cannot be in line with a rationalization of production.

[5] Additionally the underlying institutional framework in which market processes develop is taken as given, which departed strongly from the comparative institutional analysis in the works of the classics (Smith, Bastiat, Say, Mill).

[6] Schumpeter [SCHUMPETER] outlines the process of disrupting innovations and creative destruction by entrepreneurs, while Kirzner [KIRZNER] focuses on entrepreneurs as being alert to new emerging market opportunities.

[7] Don Lavoie [LAVOIE] argues in line with Hayek and Mises that the information deficit or knowledge problem applies to comprehensive forms of economic planning like in socialist countries, but also to today’s less comprehensive forms of economic planning by bureaucratic authorities.

[8] Elinor Ostrom [OSTROM] reviewed various examples where the tragedy of the commons applied and found diverse solution and coordination mechanisms. Often they were more in line with the seeing-like-a-citizen mentality and involved private and community based solutions, instead of top-down government policies.

[9] Also the political consensus in the EU to add additional sectors, e.g. where fossil fuels are used (traffic and heating) and starting to address the emissions of these sectors in the EU ETS, seems not to be fully formed.

References

[MENGER] Carl Menger, Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre, 1871.

[DALES] J. H. Dales, Pollution, Property and Prices, Toronto, 1968.

[MISES] Ludwig von Mises, Socialism: An Economic and Sociological Analysis. Jena, Germany: Gustav Fischer Verlag.

[SCHUMPETER] Josef Schumpeter, The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. New Brunswick: Transaction publishers, [1934] 2012.

[KIRZNER] Israel Kirzner, Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1973.

[LAVOIE] Don Lavoie, National Economic Planning: What is Left?. Cato Institute, 1985.

[OSTROM] Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

2nd revised edition, Munich, December 2021

Leave a Comment